About Shared Decision Making

Shared Decision Making

As clinicians, patients often rely on you to help guide their healthcare decisions. By involving patients in the

decision-making process, you can provide treatment options that align with your patients' values, preferences and

lifestyles, leading to greater patient satisfaction. This process, known as shared decision making (SDM), involves

you providing your medical expertise and your patients conveying their care preferences and values. Together, you

arrive at a mutually agreed-upon decision.

As clinicians, patients often rely on you to help guide their healthcare decisions. By involving patients in the

decision-making process, you can provide treatment options that align with your patients' values, preferences and

lifestyles, leading to greater patient satisfaction. This process, known as shared decision making (SDM), involves

you providing your medical expertise and your patients conveying their care preferences and values. Together, you

arrive at a mutually agreed-upon decision.

Integrating SDM into clinical practice improves patient engagement and assures patients are well-informed about the benefits and risks of different treatment options. SDM is particularly valuable in scenarios with multiple treatment options and no single “right” choice, often termed “preference-sensitive” conditions. Clinical decision aids can help facilitate these discussions between you and your patients and their caregivers.

In the past, most decision aids lacked a cost component. Research has shown that patients and caregivers value knowing healthcare costs for services.[1] With generous grant funding, FAIR Health pioneered new SDM tools that integrate cost information into certified decision aids to close this gap.

FAIR Health’s suite of SDM tools can be freely accessed on FAIR Health’s free, award-winning consumer website, FAIR Health Consumer (fairhealthconsumer.org) and FAIR Health for Older Adults (FAIRHealthOlderAdults.org), a dedicated section on the consumer website to provide older adults and their caregivers with resources and educational content to help them navigate the healthcare system.

Alzheimer’s Toolkit

FAIR Health’s Shared Decision-Making Initiatives

In 2021, The John A. Hartford Foundation (JAHF) awarded FAIR Health funding for its project “A National Initiative to Advance Cost Information in Shared Decision Making for Serious Health Conditions” with the goal of expanding FAIR Health’s repository of consumer-oriented tools, resources and educational content. As part of the initiative, FAIR Health created FAIR Health for Older Adults, a dedicated section on FAIR Health Consumer with information, tools and resources for older patients, family caregivers and care partners. Additionally, FAIR Health developed and launched 11 new tools, including SDM tools for hip osteoarthritis (surgical and nonsurgical), spinal stenosis, early-stage breast cancer and fast-growing prostate cancer; TTC tools for Alzheimer’s disease, heart failure and rheumatoid arthritis; and updates to existing SDM tools for palliative conditions. FAIR Health’s project findings were published in a report that was released in February 2023.

FAIR Health’s current project, “A National Initiative to Advance Cost Information in Shared Decision Making for Older Adults: Phase II Implementation Project,” also generously funded by JAHF, builds on the prior planning grant. In January 2024, FAIR Health launched Healthy Decisions for Healthy Aging, a national campaign to promote and disseminate FAIR Health’s groundbreaking educational tools and resources for older adults and their caregivers on FAIR Health for Older Adults. The campaign features inviting messaging and visuals designed to empower a diverse audience of older adults and their caregivers to make educated healthcare decisions. Campaign messaging positions FAIR Health for Older Adults as an online resource that helps older adults make “healthy decisions for healthy aging” and recognizes that for older adults, healthcare decisions are “family decisions, life-changing decisions and shared decisions.” Details about the campaign can be found here.

In June 2021, the New York Health Foundation awarded FAIR Health a grant to develop and launch decision aids to facilitate shared decision making among people of color in New York. In May 2022, FAIR Health launched the SDM tools for uterine fibroids (procedures and medications), slow-growing prostate cancer and type 2 diabetes, conditions that disproportionately affect people of color, along with educational content, resources and patient checklists on FAIR Health Consumer. A report with project findings was released in November 2022.

In March 2020, with generous funding from The New York Community Trust, FAIR Health first launched its’ groundbreaking SDM tools that combined clinical and cost information. These tools were designed to support seriously and chronically ill patients and their caregivers in SDM with clinicians for three palliative care scenarios. In collaboration with recognized SDM expert Professor Glyn Elwyn of the Dartmouth Institute, FAIR Health added cost information to clinical decision aids for dialysis, nutrition options and ventilator options on FAIR Health Consumer. The 18-month project resulted in a brief on shared decision making that summarized the project findings.

With a generous grant from The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, FAIR Health developed an educational website, FAIR Health Provider (fairhealthprovider.org), on SDM aimed at providers and clinicians who serve older adults with serious illnesses and are facing critical palliative care decisions. FAIR Health developed the provider-oriented website with the significant input of experts in palliative care and SDM. FAIR Health Provider offers guidance on integrating SDM in discussions with patients and caregivers when making decisions related to palliative care. A report about the findings from the evaluation of the initiative was released in February 2022.

Patient Resources

Explore the other tools and features listed below or on FAIR Health Consumer and FAIR Health for Older Adults that may be helpful to your patients and their caregivers, including our new Toolkit for Healthy Aging.

- Shared Decision-Making Checklist for Patients

- Shared Decision-Making Checklist for Family Caregivers and Care Partners

- Healthcare Navigation Checklist for Patients

- Healthcare Navigation Checklist for Family Caregivers and Care Partners

- FH® Medical Cost Lookup Tool

- FH® Dental Cost Lookup Tool

- FH® Total Treatment Cost Tool

- FH® Insurance Basics Articles

- Shoppable Services Lookup Tool

- Body Part Procedure Locator

- External Resources

References

- 1. Meron Hirpa et al., “What Matters to Patients? A Timely Question for Value-Based Care,” PLOS ONE 15, no. 7 (July 9, 2020): e0227845, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227845.

Section 1: Introduction to Shared Decision Making

History of Shared Decision Making

The concept of shared decision making (SDM) in medicine—the discussion between patients and/or caregivers and healthcare providers regarding various treatment options—dates back to the mid-20th century, when SDM was first developed as the idea of mutual participation between healthcare providers and patients.[1] Since then, the concept has developed further through the creation of different care frameworks that stress the importance of active patient participation.[2]

Gionfriddo et al. summarize SDM’s origins and evolution on the national and international stages,[3] including the pivotal 1982 Presidential Commission that recognized “shared decision making” as a concept and deemed it to be the “appropriate ideal for patient-professional relationships”[4] and the 2010 Salzburg Statement on Shared Decision Making, created by 18 countries, including the United States, that called for the implementation of SDM frameworks in patient care.[5] In its 2001 report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institute of Medicine discussed the adoption of shared decision making within a patient-centered care model.[6]

Legislation and other initiatives that support the use of SDM in the United States currently include:

- A Washington State law (2007) that supports the use of SDM and decision aids in medical care to advance provider-patient communication and certifies specific decision aids to assist SDM.[7]

- The Affordable Care Act of 2010, which mentions and supports the use of SDM and decision aids in medical encounters.[8]

- The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which in 2018, required the use of decision aids in at least one encounter specifically geared toward shared decision making when considering the use of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) for certain patients.[9] CMS also requires the use of decision aids in the following clinical scenarios: percutaneous left atrial closure for non-valvular atrial fibrillation[10] and lung cancer screening for beneficiaries who meet certain criteria.[11]

Impact of SDM

SDM helps increase patient understanding of treatment options, risks and benefits. Research suggests that when decision aids are used, they increase the inclusion of patients’ values in treatment decisions and have a positive effect on patient participation.[12] A study in 2016 showed that when SDM was utilized, patients were twice as likely to be involved in the medical decision and knew more about their conditions.[13] Studies have shown that when decision aids are used as part of SDM, patients may choose treatment plans that are less invasive[14] and may be more likely to comply with treatment plans and have improved outcomes, as found in a study of asthma patients who participated in SDM discussions with their clinicians.[15]

Notably, there are no significant differences in encounter times for practitioners who implement SDM and those who do not.[16]

Sensitive communication approaches that are responsive to different patient populations can help mitigate challenges to shared decision making that arise due to lower healthcare literacy; racial, ethnic or religious differences; and language or cultural differences.[17] SDM discussions can influence and enhance patient trust,[18] which may be hampered by language barriers or cultural differences in autonomy and autonomous medical decision making.[17][19]

Shared Decision Making, Costs and Financial Toxicity

Shared decision making shows promise for reducing healthcare costs[20][21] and for improving decision making without having an adverse effect on clinical outcomes.[22] This is especially important considering the growing issue of “financial toxicity”—the financial burden patients experience with medical costs, which can lead to diminished access to care and a reduced quality of life.[23] Such costs have emerged as a concern for patients, especially those receiving cancer treatment. In a study of 1,513 metastatic breast cancer patients, 98 percent of uninsured patients had forgone or postponed treatment due to cost concerns, as had 41 percent of insured patients. However, 53 percent of insured patients reported emotional hardship because of unknown treatment costs.[24] In a similar study on breast cancer patients, although 79 percent of patients preferred to know the treatment’s cost before starting medical care, 78 percent said they had not discussed costs with their providers.[25] Research suggests that open conversations about treatment costs may strengthen the relationship between provider and patient, which may in turn increase compliance with treatment plans.[26] Research further suggests that using decision aids with information about treatment costs leads to cost discussions more often than using decision aids that do not contain cost information.[27]

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of shared decision making,[28] especially regarding ventilator use.[29] In the United States, from February 1 to April 30, 2020, the number of advance directives, a form that allows patients to indicate their end-of-life care preferences, nearly quintupled when compared with January 1, 2019, to January 31, 2020.[30]

Preference-Sensitive and Chronic Conditions

In addition to its efficacy in scenarios pertaining to serious illnesses, shared decision making has been shown to be effective for certain preference-sensitive conditions[31]—preference-sensitive care is “medical care for which the clinical evidence does not clearly support one treatment option and the appropriate course of treatment depends on the values of the patient or the preferences of the patient, caregivers or authorized representatives regarding the benefits, harms and scientific evidence for each treatment option.”[8] A shared decision-making study from 2013 found that, of a group of patients with such conditions who were followed over a year, those with enhanced support from health experts had 5.3 percent lower overall medical costs, 12.5 percent fewer hospital admissions and 9.9 percent fewer preference-sensitive surgeries.[32]

Patients with chronic conditions may face challenges in managing their chronic diseases, and as such, may especially benefit from shared decision-making conversations while managing their conditions. Patients may minimize the impact of their condition on their lives, and their symptoms may not directly affect their daily activities.[33] Because action plans for managing chronic conditions may vary based on patients’ preferences, and patients with chronic conditions may be vulnerable and have multiple medical decisions to make, discussions that involve shared decision making, including finding out what matters most, may be an important determinant for engaging patients in their health decisions and enabling them to better manage their chronic conditions.[34] In the context of chronic disease management, shared decision making may not be a one-time discussion, but rather a longer-term conversation over the course of a disease. A systematic review of 39 shared decision-making studies revealed overall patient satisfaction and positive results in behavioral measures (such as reaching a decision).[35] With shared decision making, especially concerning chronic conditions, patients may have a better understanding of risks and benefits and make better decisions.[36][37]

Shared Decision Making among Patients of Color

Patients of color experience lower quality care, less empathy and poorer outcomes, and report perceived discrimination in healthcare settings due to race, ethnicity or level of English-language proficiency.[38] In addition, people belonging to racial minority groups have reported disrespect and discrimination in healthcare[39] and distrust of providers.[40] Shared decision making shows promise for engaging patients of color in their healthcare decisions, promoting communication between patients of color and their providers and building more trust in providers by patients of color.

A systematic review showed that using decision aids improved communication between providers and minority patients and decision quality outcomes, e.g., decision satisfaction.[41] Decision support via telephone about prostate cancer for Black, predominantly immigrant men led to less conflict in decision making, greater likelihood of speaking with a provider about testing and greater knowledge about prostate cancer.[42] A study of clinical outcomes for uterine fibroid treatments found no statistical difference in outcomes among three treatment methods.[43] As a result, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) conducted a follow-up study to implement SDM using decision aids among patients with uterine fibroids as part of routine care for patients with fibroids. This initiative allowed patients to choose a treatment option that aligned with their preferences.[44]

Research suggests that patients of color may not experience shared decision making with their providers as frequently as white patients due to race-related and physician-related barriers.[45] To help address this, FAIR Health, in collaboration with Dr. Chima Ndumele, an associate professor of health policy at the Yale School of Public Health and a faculty associate at the Institute for Social and Policy Studies at Yale University, undertook an initiative to advance shared decision making in clinical areas relevant to patients of color, including African Americans and other minority populations, in New York State. As a result, this website offers Option GridTM decision aids with added FAIR Health cost data that pertain to conditions that most affect patients of color: uterine fibroids, slow-growing prostate cancer and type 2 diabetes. Conditions for which tools would be offered were selected following feedback sessions with patients and public health experts.

Summary

Although patients in the United States shoulder a significant portion of their healthcare costs, research suggests that they may not perceive their care decisions to be “right.”[46] SDM helps to assure that tests, treatment and care will be based on clinical evidence that balances risks and expected outcomes with patient preferences and values,[47] generally involving the use of evidence-based strategies and patient materials called decision aids.

- SDM has been known to increase patient engagement and shows promise for reducing healthcare costs and helping to address financial toxicity. While time has been cited as a provider concern, encounter times have not been shown to take longer when shared decision making is conducted.

- SDM tools that are designed to be easy to understand can be useful for patient populations with low levels of health literacy and health insurance literacy.

- FAIR Health offers shared decision-making tools for your reference on the website here, and for patients, on FAIR Health Consumer. The tools were designed for seriously ill patients facing three life-sustaining scenarios: breathing with a ventilator (whether to continue or remove), kidney dialysis for patients with end-stage renal disease (whether to stay on or stop) and nutrition options.

- FAIR Health also offers shared decision-making tools for preference-sensitive conditions, such as uterine fibroids, type 2 diabetes and slow-growing prostate cancer—conditions that most commonly affect patients of color.

References List

- 1. Thomas S. Szasz and Marc H. Hollender, “A Contribution to the Philosophy of Medicine: The Basic Models of the Doctor-Patient Relationship,” American Medical Association Archives of Internal Medicine 97, no. 5 (May 1956): 585–592, https:doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1956.00250230079008.

- 2. Graham Meadows, “Shared Decision Making: A Consideration of Historical and Political Contexts,” World Psychiatry 16, no. 2 (June 2017): 154–155, https:doi.org/10.1002/wps.20413.

- 3. Michael Gionfriddo et al., “Shared Decision-Making and Comparative Effectiveness Research for Patients with Chronic Conditions: An Urgent Synergy for Better Health,” Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research 2, no. 6 (November 4, 2013): 595–603, https:doi.org/10.2217/cer.13.69.

- 4. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Behavioral Research, Making Health Care Decisions: The Ethical and Legal Implications of Informed Consent in the Patient–Practitioner Relationship: Volume One: Report (US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, October 1982), 30, https://archive.org/details/makinghealthcare01unit/mode/2up.

- 5. “The Salzburg Statement on Shared Decision Making,” Society for Participatory Medicine, February 7, 2011, https://participatorymedicine.org/epatients/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2011/03/Salzburg-Statement.pdf.

- 6. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, 2001, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25057539/.

- 7. Washington State Legislature, Engrossed Second Substitute Senate Bill 5930, State of Washington, 60th Legislature, 2007 Regular Session, March 5, 2007, https://apps.leg.wa.gov/documents/billdocs/2007-08/Pdf/Bills/Senate%20Bills/5930-S2.E.pdf.

- 8. United States Government, The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-111hr3590enr/pdf/BILLS-111hr3590enr.pdf.

- 9. “Decision Memo: Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs),” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), February 15, 2018, https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=288.

- 10. “Decision Memo: Final Decision Memorandum for Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Closure (LAAC),” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), February 16, 2016, https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=281.

- 11. “Decision Memo: Screening of Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT),” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), February 5, 2015, https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274.

- 12. Dawn Stacey et al., “Decision Aids for People Facing Health Treatment or Screening Decisions,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2024, no. 1 (January 29, 2024), https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd001431.pub6.

- 13. Erik P Hess et al., “Shared Decision Making in Patients with Low Risk Chest Pain: Prospective Randomized Pragmatic Trial,” BMJ 355 (December 5, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6165.

- 14. Larry A. Allen et al., “Effectiveness of an Intervention Supporting Shared Decision Making for Destination Therapy Left Ventricular Assist Device: The DECIDE-LVAD Randomized Clinical Trial,” JAMA Internal Medicine 178, no. 4 (April 1, 2018): 520, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8713.

- 15. Sandra R. Wilson et al., “Shared Treatment Decision Making Improves Adherence and Outcomes in Poorly Controlled Asthma,” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 181, no. 6 (March 15, 2010): 566–77, https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200906-0907oc.

- 16. Marleen Kunneman et al., “Assessment of Shared Decision-Making for Stroke Prevention in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” JAMA Internal Medicine 180, no. 9 (September 1, 2020): 1215–24, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2908.

- 17. Sarah T. Hawley and Arden M. Morris, “Cultural Challenges to Engaging Patients in Shared Decision Making,” Patient Education and Counseling 100, no. 1 (January 2017): 18–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.008.

- 18. Monica E. Peek et al., “Patient Trust in Physicians and Shared Decision-Making among African-Americans with Diabetes,” Health Communication 28, no. 6 (August 2013): 616–23, https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2012.710873.

- 19. Sabrina F. Derrington, Erin Paquette and Khaliah A. Johnson, “Cross-Cultural Interactions and Shared Decision-Making,” Pediatrics 142, supplement no. 3 (November 2018): S187–92, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0516j.

- 20. Emily Oshima Lee and Ezekiel J. Emanuel, “Shared Decision Making to Improve Care and Reduce Costs,” New England Journal of Medicine 368, no. 1 (January 3, 2013): 6–8, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1209500.

- 21. David Arterburn et al., “Introducing Decision Aids at Group Health Was Linked to Sharply Lower Hip and Knee Surgery Rates and Costs,” Health Affairs 31, no. 9 (September 2012), https:doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0686.

- 22. Megan E Branda et al., “Shared Decision Making for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Trial in Primary Care,” BMC Health Services Research 13, no. 1 (August 8, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-301.

- 23. “NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms: Financial Toxicity,” National Cancer Institute, accessed August 29, 2024, https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/financial-toxicity.

- 24. Stephanie B. Wheeler et al., “Cancer-Related Financial Burden among Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 36, no. 30 supplement (October 20, 2018): 32–32, https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2018.36.30_suppl.32.

- 25. Rachel Adams Greenup et al., “The Costs of Breast Cancer Care: Patient-Reported Experiences and Preferences for Transparency,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 36, no. 30 supplement (October 20, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.30_suppl.207.

- 26. Thomas H Gallagher and Wendy Levinson, “A Prescription for Protecting the Doctor-Patient Relationship,” The American Journal of Managed Care 10, no. 2, part 1 (February 1, 2004): 61–68, https://www.ajmc.com/view/feb04-1703p61-68.

- 27. Mary C. Politi et al., “Encounter Decision Aids Can Prompt Breast Cancer Surgery Cost Discussions: Analysis of Recorded Consultations,” Medical Decision Making 40, no. 1 (December 12, 2019): 62–71, https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x19893308.

- 28. Elissa M. Abrams et al., “The Challenges and Opportunities for Shared Decision Making Highlighted by COVID-19,” The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 8, no. 8 (September 2020): 2474–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.003.

- 29. Nicholas Simpson, Sharyn Milnes and Daniel Steinfort, “Don’t Forget Shared Decision‐Making in the COVID-19 Crisis,” Internal Medicine Journal 50, no. 6 (June 14, 2020): 761–63, https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.14862.

- 30. Catherine L. Auriemma et al., “Completion of Advance Directives and Documented Care Preferences during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic,” JAMA Network Open 3, no. 7 (July 20, 2020): e2015762, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15762.

- 31. Annette M. O’Connor, Hilary A. Llewellyn-Thomas and Ann Barry Flood, “Modifying Unwarranted Variations in Health Care: Shared Decision Making Using Patient Decision Aids,” Health Affairs 23, supplement no. 2 (October 7, 2004): VAR-63-VAR-72, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.var.63.

- 32. David Veroff, Amy Marr and David E. Wennberg, “Enhanced Support for Shared Decision Making Reduced Costs of Care for Patients with Preference-Sensitive Conditions,” Health Affairs 32, no. 2 (February 2013): 285–93, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0941.

- 33. Cathleen E. Morrow and Sheri Reder, Shared Decision Making for Chronic Conditions and Long-Term Care Planning, SHARE Approach Webinar Series, no. 6, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), July 26, 2016, https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/webinars/sharewebinar716-slides.pdf.

- 34. Terri R. Fried, Richard L. Street and Andrew B. Cohen, “Chronic Disease Decision Making and ‘What Matters Most,’” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 68, no. 3 (March 2020): 474–77, https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jgs.16371.

- 35. L. Aubree Shay and Jennifer Elston Lafata, “Where Is the Evidence? A Systematic Review of Shared Decision Making and Patient Outcomes,” Medical Decision Making 35, no. 1 (January 2015): 114–31, https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x14551638.

- 36. A.M. Stiggelbout, A.H. Pieterse and J.C.J.M. De Haes, “Shared Decision Making: Concepts, Evidence, and Practice,” Patient Education and Counseling 98, no. 10 (October 2015): 1172–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022.

- 37. Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, The Consumer Benefits of Patient Shared Decision Making, Research Brief 37, May 2019, https://www.healthcarevaluehub.org/application/files/8115/6367/3510/RB_37_-_Shared_Decision_Making.pdf.

- 38. Institute of Medicine, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2003), https://doi.org/10.17226/12875.

- 39. Janice Blanchard and Nicole Lurie, “R-E-S-P-E-C-T: Patient Reports of Disrespect in the Health Care Setting and Its Impact on Care,” Journal of Family Practice 53, no. 9 (September 1, 2004): 721, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2004/sep/r-e-s-p-e-c-t-patient-reports-disrespect-health-care-setting.

- 40. Elizabeth A. Jacobs et al., “Understanding African Americans’ Views of the Trustworthiness of Physicians,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 21, no. 6 (June 2006): 642–47, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00485.x.

- 41. Aviva G. Nathan et al., “Use of Decision Aids with Minority Patients: A Systematic Review,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 31, no. 6 (March 17, 2016): 663–76, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3609-2.

- 42. Stephen J. Lepore et al., “Informed Decision Making about Prostate Cancer Testing in Predominantly Immigrant Black Men: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 44, no. 3 (December 2012): 320–30, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-012-9392-3.

- 43. Evan Myers, Donna Messner and Priscilla Velentgas, Which Treatments for Uterine Fibroids Have the Best Results? Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Final Research Report, 2018, https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Velentgas002-Final-Research-Report.pdf.

- 44. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), Using a Decision Aid to Help Patients Make Decisions about Fibroid Treatment, last updated August 8, 2024, https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2018/using-decision-aid-help-patients-make-decisions-about-treatment-fibroids.

- 45. Monica E. Peek et al., “Race and Shared Decision-Making: Perspectives of African-Americans with Diabetes,” Social Science & Medicine 71, no. 1 (July 2010): 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.014.

- 46. Brian J. Zikmund-Fisher et al., “Deficits and Variations in Patients’ Experience with Making 9 Common Medical Decisions: The DECISIONS Survey,” Medical Decision Making 30, no. 5, supplement (September 2010): 85–95, https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x10380466.

- 47. National Learning Consortium, Fact Sheet: Shared Decision Making, December 2013, https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/nlc_shared_decision_making_fact_sheet.pdf.

Section 2: Shared Decision Making: What Is Involved?

The shared decision-making (SDM) process can occur over the course of one or more conversations and is a collaborative effort between you (the healthcare provider), the patient and the caregiver or family member. SDM generally involves setting the stage for team-based decision making by supporting the patient when discussing choices, identifying the patient’s goals, discussing the risks and benefits of treatment options and, finally, making a decision with the patient and/or caregiver.

While SDM models largely convey a similar process of collaborative decision making, patients and providers can choose to use the model that is most helpful to them. One approach, developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), is the SHARE approach, which includes the following five steps for shared decision making: Seek your patient’s participation; Help your patient explore and compare treatment options; Assess your patient’s values and preferences; Reach a decision with your patient; and Evaluate your patient’s decision.[1]

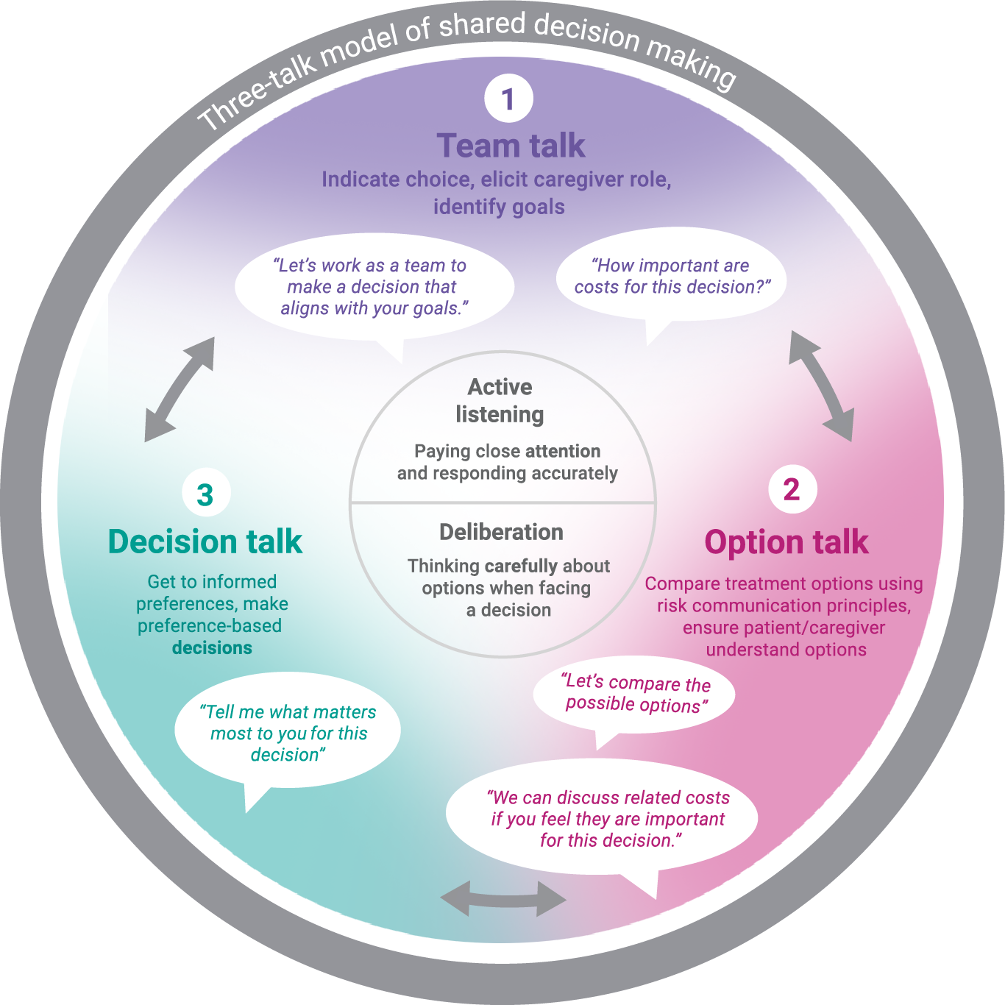

Another approach is the three-talk model, developed by Dr. Glyn Elwyn of the Dartmouth Institute and modified by FAIR Health to reflect cost conversations (Figure 1).[2] The model encapsulates the different steps for achieving shared decision making collaboratively.

Three-Talk Model of Shared Decision Making, Adapted for Cost Conversations

What You Can Do:

- Invite participation Encourage the patient and, if relevant, their caregiver(s) to actively participate in the decision-making process.

- Discuss roles Clearly outline the roles of the patient and caregiver(s), as relevant, in making decisions. The caregiver’s role may largely depend on the patient’s cognitive ability.

- Assess cognitive abilities to make healthcare decisions Evaluate the patient’s cognitive abilities if needed; involve the caregiver(s) as appropriate.

- Find What Matters Discuss the patient’s treatment goals and preferences.[3] Determine whether the cost of treatment is a significant factor for them.

- Ask open-ended questions Encourage the patient to articulate their thoughts and concerns.

What You Can Say:

- “Let’s work as a team to make a decision that suits you best.”[2]

- “What are your goals for this decision?”[3]

- “What are you hoping for in life?”[3]

- “What are you most afraid of losing in life?”[3]

- “How important are costs for this decision?”

- “To what extent are costs of treatment a factor in this decision?”

- “What is most important to you for this decision?”

What You Can Do:

- Utilize tools: Refer to SDM tools on FAIR Health Consumer or FAIR Health for Older Adults when explaining treatment options to patients.

- Simplify language: Use easy-to-understand language for clarity and visual aids where appropriate.

- Discuss costs: If costs are a concern, use the SDM, TTC (total treatment cost) or medical cost lookup tools.

- Explain risks statistically: Use numbers rather than descriptive words and relative risks.

- Balance information: Present positive and negative outcomes equitably and use your clinical judgement.

- Check for understanding: Observe whether the patient has trouble making a decision and use the “teach-back” method to verify understanding (see below).

What You Can Say:

- “Let’s compare the possible options.”[2]

- “These options may have different effects for you compared with others, so I want to describe the options and their effects.”[1]

- “We can discuss related costs if you feel they are important for this decision.”

- “Some people may find that cost may matter more to them. If that is the case, we can go over how the costs compare for the clinical options. If you would like to know the costs, we can do that here, or I can refer you to someone who can discuss this with you.”

- “We have discussed different options for [your condition]. So that I can make sure I explained them clearly, can you tell me how they are different?”[1]

- “I would like to know how well I explained the options for treatment. Could you tell me how you understand the treatment choices I’ve presented [for your condition]?”[1]

- “We talked about [name the options]. Would you be able to tell me how you would explain them to someone?”

- “When you think about these options, what matters most to you?”[1]

- “Comparing the possible risks, what matters most to you? What worries you the most?”[1]

Check for Understanding

- Observe decision-making Look for signs that the patient or caregiver(s) may be struggling to make a decision.

- Use “teach-back” method Verify understanding by asking the patient to explain the treatment options back to you.

What You Can Do:

- Collaborate on decisions: Drawing on your medical expertise, help the patient make a decision that aligns with his or her values, goals and preferences.

What You Can Say:

Further Reading

- Winnie C. Chi et al., “Multimorbidity and Decision-Making Preferences among Older Adults,” The Annals of Family Medicine 15, no. 6 (November 2017): 546–51, https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2106.

- Thomas W. LeBlanc et al., “Triadic Treatment Decision-Making in Advanced Cancer: A Pilot Study of the Roles and Perceptions of Patients, Caregivers, and Oncologists,” Supportive Care in Cancer 26, no. 4 (November 4, 2017): 1197–1205, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3942-y.

- C. Feuz, “Shared Decision Making in Palliative Cancer Care: A Literature Review,” Journal of Radiotherapy in Practice 13, no. 3 (November 8, 2013): 340–49, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1460396913000460.

- Cathy Charles, Amiram Gafni and Tim Whelan, “Shared Decision-Making in the Medical Encounter: What Does It Mean? (Or It Takes at Least Two to Tango),” Social Science & Medicine 44, no. 5 (March 1997): 681–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3.

- Mirjam M. Garvelink et al., “A Synthesis of Knowledge about Caregiver Decision Making Finds Gaps in Support for Those Who Care for Aging Loved Ones,” Health Affairs 35, no. 4 (April 2016): 619–26, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1375.

- Mathy Mezey, “Decision Making in Older Adults with Dementia,” Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing (HIGN) Dementia Series 9 (2016), https://hign.org/consultgeri/try-this-series/decision-making-older-adults-dementia.

- J. Paling, “Strategies to Help Patients Understand Risks,” BMJ 327, no. 7417 (September 27, 2003): 745–48, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7417.745.

- David Laight, “Risk Communication: A Pillar of Shared Decision Making,” Prescriber 33, no. 6 (June 2022): 24–28, https://doi.org/10.1002/psb.1993.

- Daniel J. Morgan, Laura D. Scherer and Deborah Korenstein, “Improving Physician Communication about Treatment Decisions,” JAMA 324, no. 10 (March 9, 2020): 937–38, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.0354.

References List

- 1. “The SHARE Approach: Essential Steps of Shared Decisionmaking: Expanded Reference Guide with Sample Conversation Starters (Workshop Curriculum: Tool 2),” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), accessed August 28, 2024, https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/tools/tool-2/share-tool2.pdf.

- 2. Glyn Elwyn et al., “A Three-Talk Model for Shared Decision Making: Multistage Consultation Process,” BMJ 359, no. 359 (November 6, 2017): j4891, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4891.

- 3. Glyn Elwyn et al., “Goal-Based Shared Decision-Making: Developing an Integrated Model,” Journal of Patient Experience 7, no. 5 (2020): 688–96, https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373519878604.

Section 3: Using Shared Decision-Making Tools

FAIR Health’s shared decision-making (SDM) tools integrate clinical and cost information to support patient-centered decision making, emphasizing a balance between clinicians’ expertise and patients’ preferences. It is crucial to note that while SDM tools provide valuable insights, they do not replace medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

FH® Total Treatment Cost (TTC) tools offer comprehensive cost information for bundled annual care expenses related to chronic conditions, medical procedures or acute events. TTC tools serve to aid patients and their caregivers in financial planning and understanding medical bills.

Here is a brief, technical, step-by-step guide on how to access and utilize FAIR Health's SDM and TTC tools. For more detailed information, refer to the FAIR Health Clinical Implementation Toolkit for Providers.

- 1. Navigate to FAIR Health for Older Adults and proceed to the SDM section. From there, choose the desired tool from the drop-down menu under “Select a Decision Aid” and click on the "View" button to access it. If utilizing TTC tools, head to the TTC tool section, choose the relevant tool from the options listed under “Select a condition or event-based procedure,” and then click on the “View” button.

- 2. Start by entering your institution or healthcare facility’s zip code, i.e., where patient care is received. FAIR Health’s database of healthcare claim records corresponds to the zip code billed by providers.

- 3. For SDM tools, a series of “Patient Questions” are displayed to guide the SDM discussion and inform the patient of treatment options. Under “What does the option involve?” you'll find a brief description of each option along with a “See the cost” button.

- 4. Upon clicking “See the cost,” you will be prompted to agree to the Terms of Use before accessing cost information. This agreement outlines the usage terms and provides licensing information regarding the current procedural terminology (CPT®)1 codes associated with the cost estimates.

- 5. The cost estimates for the selected treatment option (SDM tools) or total annual care costs for specific conditions, procedures or events (TTC tools) will be displayed. You may click back and access other treatment pathways or conditions.

Understanding the Cost Information

The cost estimates default to the 80th percentile. For out-of-network or uninsured costs, this means that 80 percent of providers in the area charge equal to or less than the estimate, while 20 percent charge equal to or more than the estimate. In-network costs represent what a health plan will pay a provider for services within the network. Similarly, these estimates are also set at the 80th percentile, indicating that 80 percent of the allowed amounts are equal to or less than the estimate, while 20 percent are equal to or more than the estimate.

Medicare pricing reflects the amount that Original Medicare allows for a treatment or procedure in the specific zip code area. However, this price does not account for rates paid by Medicare Advantage, commercial or Medicaid plans.

The cost estimates do not account for individual health plans’ specifics, deductibles, copays or coinsurances. Patients are responsible for out-of-pocket costs unless covered by supplemental policies. FH® Insurance Basics offers educational resources to help patients understand their healthcare costs and navigate insurance-related matters.

1 CPT © 2023 American Medical Association (AMA). All rights reserved.

Section 4: Further Reading and Additional Resources

SDM Implementation Resources

- Glyn Elwyn et al., “A Three-Talk Model for Shared Decision Making: Multistage Consultation Process,” BMJ 359 (November 2017): j4891, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4891.

- Glyn Elwyn et al. “Shared Decision Making: A Model for Clinical Practice,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 27, no. 10 (October 2012):1361-1367, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6.

- AHRQ:

- AHRQ SHARE Approach to Shared Decision Making: This resource offers examples of questions that can be asked and examples for risk communication during shared decision making.

- The Caregiver Role in Shared Decision-Making with Persons Living with Dementia: The Human Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) outlines the role of the caregiver in SDM conversations for patients with dementia here.

Advance Directives

An advance directive, e.g., living will and healthcare proxy documents,[43] is a written statement that documents a person’s wishes for future medical care in case the patient becomes unable to express them later.[44] Below are links to resources that you can use with patients and caregivers:

-

PREPARE for Your Care: https://prepareforyourcare.org/advance-directive

PREPARE for Your Care is a resource provided by the Institute for Healthcare Advancement that helps individuals learn about Medical Decision Making, determine their wishes and prepare to make and discuss those decisions with their care team, family and friends. The website contains pamphlets and tools to assist people in decision making, as well as legally binding advance directives in both English and Spanish. -

Five Wishes: https://fivewishes.org/

Five Wishes, a resource by Aging with Dignity, is a legal advance directive, or living will, written in user-friendly language to assist individuals in thinking about and recording their end-of-life wishes. The resource is meant to help individuals consider all aspects of their potential end-of-life needs, including medical, personal, emotional and spiritual needs, and contemplate how they would like to discuss their wishes with family, friends and medical professionals. - Clarify Code Status: It is helpful to clarify with patients beforehand whether they would want everything done to prolong their life if their condition gets worse. AHRQ offers helpful case studies of speaking about code status with patients: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/web-mm/do-you-want-everything-done-clarifying-code-status.

COVID-19-Related Resources

- The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization’s Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Shared Decision-Making Tool assists patients and caregivers in decision making related to COVID-19.

- Vitaltalk created the COVID Ready Communication Playbook, which provides tips for medical professionals on how to navigate difficult conversations regarding COVID-19.

- The Coalition for Compassionate Care of California’s COVID Conversations Toolbox aids both providers and consumers.

- The Center to Advance Palliative Care created the COVID-19 Response Resources Hub to provide shared decision-making scripts and other resources to guide medical professionals through decision making with COVID-19 patients.

Health Literacy, Health Insurance Literacy and Patient Communication

- American Medical Association: RESPECT method for patient communication: https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/6-simple-ways-master-patient-communication

- Health Literacy Universal Precautions: Steps and practices that all medical professionals should take to assure that patients understand the health information presented: https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/index.html

- For further reading:

- Kristen J. McCaffery, Sian K. Smith and Michael Wolf, “The Challenges of Shared Decision Making among Patients with Lower Literacy: A Framework for Research and Development,” Medical Decision Making 30, no. 1 (August 2010): 35-44, https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X09342279.

- Implementing Shared Decision Making with Low Health Literacy Patients, The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, December 9, 2015, https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/webinars/sdmwebinar1209-slides.pdf.

Resources for Preference-Sensitive Conditions

Type 2 Diabetes Resources

- Patient checklist

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers comprehensive resources about diabetes, treatment, education, support and more. The CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP) helps people and communities prevent chronic disease and promotes health and wellness for all.

- Diabetes Type 2 Today offers a wealth of information about risk factors, prevention and how to live with type 2 diabetes.

- The American Diabetes Association (ADA), which is dedicated to preventing, curing and managing diabetes, offers resources for anyone who might be affected by diabetes, including women, men, seniors and children. The ADA’s website offer links to medication assistance programs and advice for healthy living.

- The American Heart Association, the nation’s oldest and largest voluntary organization dedicated to fighting heart disease and stroke, offers specific information and tools regarding how type 2 diabetes can increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Diabetes Support Groups

- The Defeat Diabetes Foundation has a list of support groups in all 50 states.

- Your local Department of Health may also offer similar resources. You can find yours here.

Uterine Fibroids Resources

- Patient checklist

- Healthy Women is a nonprofit whose mission is to educate women to make informed health choices through fact-based, expert-sourced content, and creative evidence-based programming. The website offers resources related to managing uterine fibroids.

- This blog from Johns Hopkins Medicine also has more information surrounding the symptoms of fibroids, treatment, diagnosis and more. The mission of Johns Hopkins Medicine is to improve the health of the community and the world by setting the standard of excellence in medical education, research and clinical care.

- This Mayo Clinic article on uterine fibroids has information about the symptoms and treatment of fibroids. The Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization, which provides information and tools for a healthy lifestyle.

- The New York State Department of Health has a page on uterine fibroids, which details what happens with fibroids during pregnancy, as well as current and developing treatments for fibroids.

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has a list with find-a-provider resources. The NIH is the part of the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) that is the nation’s medical research agency, making important discoveries that improve health and save lives.

- MedLine Plus provides information about treatments and therapies for fibroids. MedlinePlus is a service of the National Library of Medicine (NLM), the world's largest medical library, which is part of the NIH. MedLine Plus’s mission is to present high-quality, relevant health and wellness information that is trusted, easy to understand, and free of advertising.

Slow-Growing Prostate Cancer Resources

- Patient checklist

- The Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF) offers information about treatment centers and financial assistance. The PCF’s goal is to fund research to improve the prevention, detection and treatment of prostate cancer, and ultimately, cure it for good.

- Information about causes, risk factors, detection, treatment and related topics can be found on the American Cancer Society’s website. The American Cancer Society is on a mission to free the world from cancer. It funds and conducts research, shares expert information, supports patients and spreads the word about prevention.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) web pages on prostate cancer includes basic information, statistics, health tips and more. The CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP) helps people and communities prevent chronic disease and promotes health and wellness for all.

Additional information on prostate cancer:

- This article on prostate cancer from St. Luke's Health has more information about diagnostic criteria and symptoms as well as other helpful resources.

- This book delves deeper into the science behind prostate cancer and how it’s treated.

- CancerCare provides free professional support services, including resources specifically regarding prostate cancer. Founded in 1944, CancerCare is the leading national organization providing free, professional support services and information to help people manage the emotional, practical and financial challenges of cancer.

- ZERO Cancer is a national nonprofit with the mission to end prostate cancer. ZERO Cancer advances research, improves the lives of men and families and inspires action. ZERO Cancer’s website contains toolkits, webinars, fact sheets and more for the newly diagnosed.

- [43]“Types of Advance Directives,” American Cancer Society, last revised May 13, 2019, https://www.cancer.org/treatment/finding-and-paying-for-treatment/understanding-financial-and-legal-matters/advance-directives/types-of-advance-health-care-directives.html#:~:text=The%202%20most%20common%20types%20of%20advance%20directives,you%20more%20details%20on%20these%202%20types%20below.%29.

- [44]“Advance Care Planning,” Medicare.gov, https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/advance-care-planning.